|

The Virus Loves Density:

COVID-19 and the Story of Dharavi

Vinay Lal

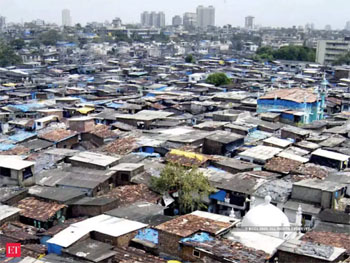

As the coronavirus continues to maul societies, confounding the scientists with its cunning and increasingly finding victims among the young, who were at first considered to be largely invulnerable, it becomes all the more necessary to look closely beyond China and most of Southeast Asia to consider whether other countries or smaller political entities have had been able to prevail in stemming the transmission of the virus. One of the most astounding stories of such success comes to us from Dharavi, as described in my recently published book, The Fury of Covid-19: The Histories, Politics, and Unrequited Love of the Coronavirus (Pan Macmillan), from where what follows is excerpted with some modifications. Dharavi is often described as the most “infamous” and largest slum in Asia, ‘a cliché of Indian misery’, before the film Slumdog Millionaire turned it into the most “famous” slum by bringing it to the attention of the West. Somewhere between 850,000 and a million people live in Dharavi, which occupies an area of less than one square mile, or about 2.5 square kilometres, with a population density of over 275,000 per sq. km. To put that in perspective, the population density of New Zealand, which has also flattened the curve, earned the envy of the world, and won accolades for its young female Prime Minister whom the New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof and late-night American comic Steve Colbert fawn over as the jewel in the crown of world leaders, is 15 per sq. km.

The Virus Loves Density: Dharavi. Source: The Economic Times (2 April 2020)

Dharavi reported its first case on April 1, and 419 cases were recorded in April; another 1,216 cases were added in May, and on July 7 only one new case was reported. The average doubling rate went up from 18 days in mid-April to 78 in mid-June. Some portion of its population consists of migrant workers, who had departed for their villages when the lockdown commenced, but by far the greater number of Dharavi’s residents were confined to the slum itself. Few people have running water; nearly everyone uses a public toilet at one of the 500 toilet complexes in Dharavi, and the wait to use a toilet can extend to an hour. Each dwelling, generally about 100 square feet in size, houses eight to ten people, sometimes more, and the daily-wage and informal workers who comprise a substantial portion of its population seldom cook at home and eat out, often from street vendors.

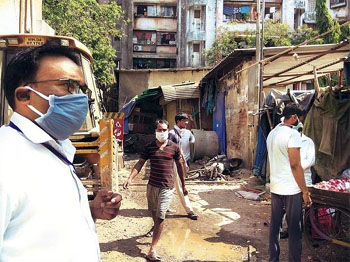

Density, not distancing, defines the possibilities of life in Dharavi. And the virus loves density. So just how did Dharavi distance itself from the virus and turn “social distancing”, against all odds, into a success—with the recognition that all such proclamations of triumph are premature—in one of the most densely inhabited clusters of human population in the world? In early May, while the virus was still on a rampage, the Washington Post reported on Dharavi and the part being played by a single mother, Laxmi Ramchandra Kamble, who is associated with the nonprofit organization, Acorn Foundation, that generally works with people who earn their living as rag-pickers and has in these times shifted its focus to offering aid and relief to a beleaguered and besieged population out of work. Kamble and the team of workers assigned to work with her distributed supplies throughout the day: packets of prepared food to some, uncooked rice and lentils to others. Perhaps, at that time of the year, the alleviation of human suffering struck the reporters as the most interesting part of the slowly emerging narrative of the virus’s journey through Dharavi. Three weeks later, the reporters working for al-Jazeera, similarly pivoting their story around one activist, the 31-year old community activist Kunal Kanase, ‘born and bred in Dharavi’, had stumbled on to the fact that the slum’s residents had been proactive in other respects. Kanase found that his neighbour less than ten feet away from his home had fallen sick, but he was unable to attract the attention of authorities, and ‘no one ever came to test or isolate the six other members of the woman’s household.’ Kanase took to hounding the authorities, and in one instance tweeted at the Mumbai police until they arrived at the doorstep of his neighbour.

Life in Dharavi in Times of the Coronavirus. Source: Business Standard (India), 6 April 2020

If Dharavi could be described as one of the central nodes of Mumbai’s informal economy, as an informal city within the city, we may analogously think of the accounts above as informal narratives that supplement the official narrative of how the coronavirus was stopped in its tracks in Dharavi. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), under whose jurisdiction Dharavi falls, took the credit for containing the virus in a press release issued in late June: ‘The BMC adopted a model of actively following four T’s—Tracing, Tracking, Testing and Treating. This approach included activities like proactive screening.’ Three days after the first case was reported, the local authorities had set up fever clinics around Dharavi: at each of these camps, a team of doctors and health care workers in protective equipment screened dozens of residents daily with infrared thermometers and pulse oximeters. By the second week of April, 47,5000 people had been screened; over 350,000 people had been screened by mid-June, if not earlier, and according to a documentary produced by WION over 700,000 people had been screened by the end of the first week of July. Hundreds of people were trained in contact tracing at the outset and the infected, rather than being ordered into self-quarantine, hardly feasible in the cramped quarters that passes for “home” for everyone in Dharavi, were pulled into marriage halls, gyms, and schools that had been converted into quarantine centers which by mid-July had housed at least 10,000 people. ‘It is possible’, as the US-based researcher Ramanan Laxminarayanhas suggested, that ‘the compact geography enabled a greater level of coordination than in other places’, but the greater insight appears to have come from the Assistant Commissioner of Police responsible for the municipal ward that includes Dharavi, Kiran Dighavkar, who explained the strategy succinctly: ‘Instead of people reporting it, we started chasing the virus.’ The WHO’s chief, Tedros Ghebreyesus, has all but suggested that the world should be emulating Dharavi and chasing the virus in a similar fashion: his laudatory message on July 10 noted, ‘There are many examples from around the world that have shown that even if the outbreak is very intense, it can still be brought back under control. And some of these examples are Italy, Spain, and South Korea, and even in Dharavi – a densely packed area in the mega city of Mumbai – a strong focus on community engagement and the basis of testing, tracing, isolating and treating all those that are sick is key to breaking the chains of transmission and suppressing the virus.’

Doctors at work in containing the coronavirus in Dharavi. Source: The Los Angeles Times, 24 June 2020; Photo copyright: Rafiq Maqbool / Associated Press

There are, however, other denser stories lurking behind these narratives of Dharavi’s success in the containment of the coronavirus, though the very brief excursus here is not necessarily intended to construe the singularity of this settlement. It is recognized if not widely known that Dharavi is a thriving beehive of industrial and entrepreneurial activity, with thousands of small-scale manufacturing units, textile and apparel factories, leather and metal workshops, plastic recycling centers, food processing businesses, and much more. This part of the story is not unimportant, compelling us to understand that Dharavi understands itself not as a “slum” but as a locus of “work”: to this extent, the suspension of economic activity has impacted this settlement as much as it has shopping malls, retail shops, or upper-end boutique stores. Some years ago, the journalist Kalpana Sharma, in Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia’s Largest Slum (2000), offered a look into another important aspect of its sociological profile. Though the Kolis, a caste of fishermen, claim Dharavi as their own as its original inhabitants when it was but a fishing village, migrant Tamil Dalits tanners in the late 19th century had the greater role to play in its development. They were followed by Kumbars, a Gujarati community of potters. The Tamilians constitute at least a third of Dharavi’s population; however, as Tamil Nadu itself became the engine of economic reform, migration from the state dwindled and the place of the Tamil migrants was taken up by migrants from Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and elsewhere. If Dharavi is something of a Tower of Babel, whose Tamilians generally speak Marathi rather well, it also has significant religious diversity: some 30 percent of the people are Muslims, another 6 percent Christians, and the remainder predominantly lower-caste Hindus or rather, to be somewhat more precise, Dalits. But it is not only in this respect, as home to a very diverse population, that Dharavi mirrors Mumbai: it shares with the rest of the city that spirit of civic-mindedness and cooperation that distinguishes this city from Delhi.

Garment factory workers in Dharavi. Source: The Guardian (25 November 2014). Photo: Suraj Uchil

For all these reasons, Dharavi’s success may perhaps be somewhat more difficult to emulate in other “slum” settlements. But Dharavi has one further characteristic that calls for comment, more particularly as it permits us to transition back into the questions with which this chapter commences. The urban geographer, Jan Nijman, has written that ‘the overwhelming majority of Dharavi residents are Dalits (formerly known as Untouchables) who combine material poverty with social stigma as soon as they move outside of their circles. They reside in tight community clusters within the slum generally based on regional origin and professional status—living anywhere else is virtually unthinkable.’ The tightly-knit communities, separated by language, are also caste-based. There is both stratification, even if the ‘overwhelming majority of Dharavi residents’, as observers are agreed, are Dalits, but complementariness, too. What part caste has played in the story of Dharavi’s tussle with the virus is as yet unknown, but it would perhaps be possible to argue that the settlement’s efforts at the containment of the virus are at least not likely to have been obstructed by sharp caste hierarchies, a consideration that may be of some importance more generally in urban environments. The fact that the upper castes will in most settings keep their distance from lower castes is scarcely beyond dispute, although in principle modern secular institutions are designed, so to speak, to diminish if not altogether eliminate the fear of pollution by touch or proximity. The coronavirus indeed introduces a new and radical element of uncertainty in what is simultaneously an old and yet modern setting: since the virus can be also be transmitted by pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, it turns every lower caste person, already laboring under the cloud of prejudice entrenched in multiple layers of history and experience, into a carrier of disease. There can be little doubt that Prime Minister Modi’s lockdown order, however much it may have inconvenienced middle class Indian households who were suddenly deprived of domestic help, the overwhelming majority of whom are not only impoverished but from lower caste groups, was also looked upon by them with enormous relief as it removed them from the proximity of those who suddenly became vectors of lethal sickness.

The book is now available worldwide through Amazon both in kindle and in paperback. Available in the US, here

And in India, here

[Vinay Lal is Professor of History and Asian American Studies at UCLA. He writes widely on the history and culture of colonial and modern India, popular and public culture in India, historiography, the politics of world history, the Indian diaspora, global politics, contemporary American politics, the life and thought of Mohandas Gandhi, Hinduism, and the politics of knowledge systems.]

Courtesy: https://vinaylal.wordpress.com/

Back to Home Page

Frontier

Oct 31, 2020

Prof. Vinay Lal VLAL@HISTORY.UCLA.EDU

Your Comment if any

|